Distance Classroom Experience 2.0

I’m not having my father’s seminary classroom experience. I’m not even having my own master’s-level graduate classroom experience. The classroom experience as a distance student in the Old Dominion University English Ph.D. program has been flipped by technology—and I mean that in a really good way!

Let me describe what a three-hour class session “looks” like.

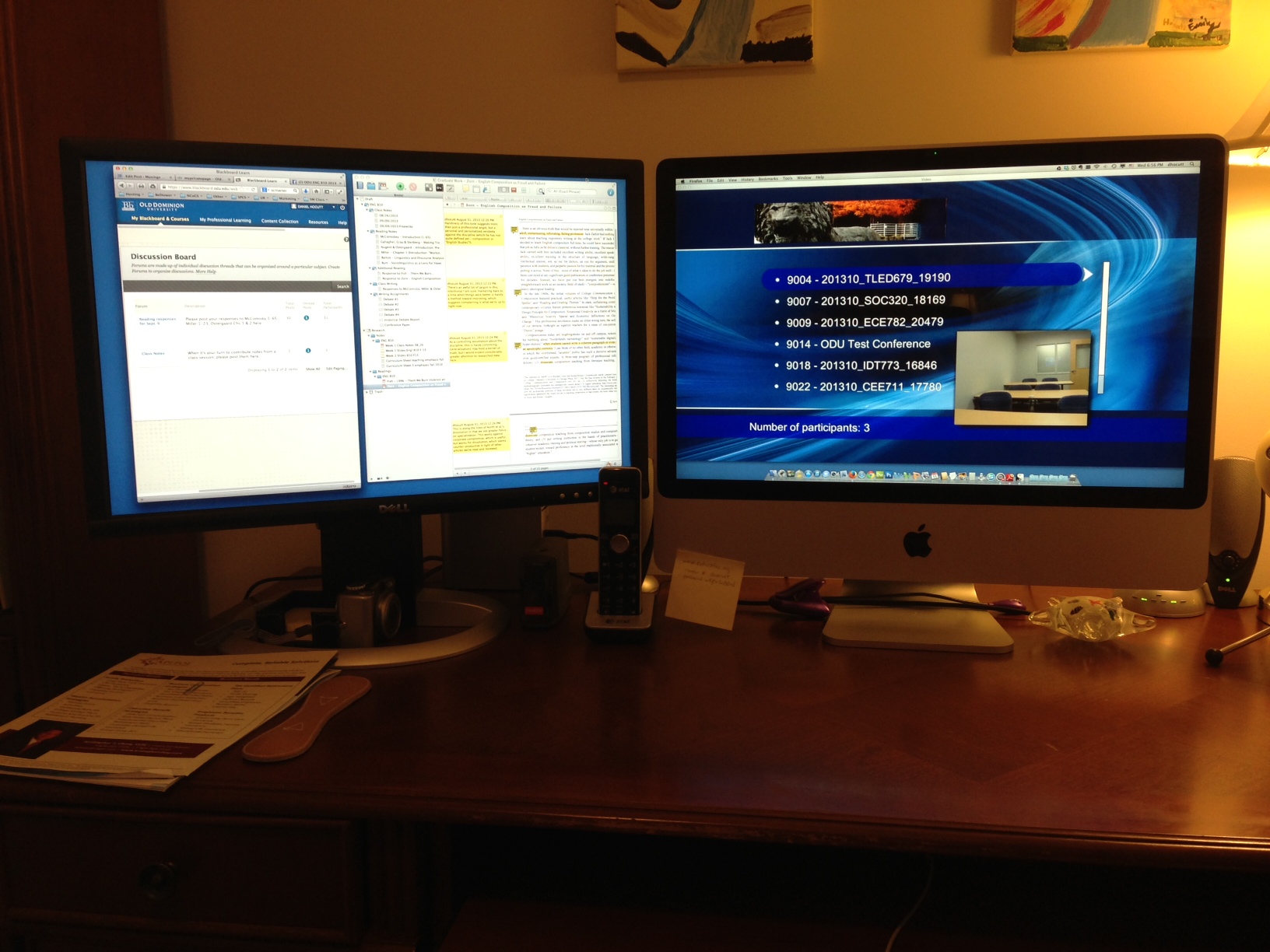

I sit in my home office in front of two 24″ monitors (an old-but-solid iMac along with a Dell monitor). I wear a headset with boom mic so my classmates and professor can hear me without yelling, and so I can hear them without subjecting the rest of my home’s inhabitants to a history and survey of English studies. On the main screen I place our classroom, which is shared as video- and voice-over-IP using Cisco’s Jabber. The classroom in Norfolk hosts 6 local students and the professor. Each of the students in the classroom has a laptop or tablet or some other device. Each also has a mic and a mic button. When a student presses the mic button, the camera pans out, then zooms in to focus on the speaker. At other times, by default, the instructor’s mic is active and the camera focused on her (Dr. Joyce Neff, in case you were wondering).

The instructor’s station includes a document reader in addition to a computer, so the instructor can switch between camera, computer monitor (for slides or video or other material), and document camera for handwritten notes and print materials. The instructor can voice over whatever is on the screen, so she can be talking while pointing to items on the computer monitor or the document camera. She can even write notes by hand using the document camera, and we can all see them in real time.

There are also 6 of us distance students. We can’t see each other unless we activate our own mics and talk, but everyone in the classroom can see us on a large monitor opposite their seats. One of the students took a picture of the monitor and shared it with us; we look a little like a Brady Bunch opening. So we’re on camera all the time unless we deliberately turn off our cameras, which seems a bad idea since there’s no other way to know we’re plugged in and engaged. We distance students generally mute our mics until we have something to say, then we activate our mics and try to jump in without interrupting too much. There’s plenty of talking over one another since we can’t tell if someone is about to say something, but all in all the process works pretty well.

There are also 6 of us distance students. We can’t see each other unless we activate our own mics and talk, but everyone in the classroom can see us on a large monitor opposite their seats. One of the students took a picture of the monitor and shared it with us; we look a little like a Brady Bunch opening. So we’re on camera all the time unless we deliberately turn off our cameras, which seems a bad idea since there’s no other way to know we’re plugged in and engaged. We distance students generally mute our mics until we have something to say, then we activate our mics and try to jump in without interrupting too much. There’s plenty of talking over one another since we can’t tell if someone is about to say something, but all in all the process works pretty well.

But that’s just one screen of information. It’s the other screen that flips the experience!

On the second monitor I have several website tabs open. First and foremost is Facebook chat. All of us (except the instructor) are engaged in back channel chatter throughout the course of the class using a Facebook group chat. About half the time we’re posting about something happening in the class at that moment, and the chatter is instructional, germane, and instantly useful. The rest of the time we’re being peanut-gallery clever, which turns out to be quite helpful during some of the more serious discussions. I also have Blackboard open so I can access notes, discussions, and other materials there. And I have Literature and Latte’s Scrivener open, where I take class notes and refer to my annotated PDF documents, my own reading notes, my bibliography, and just about everything else I’ve written. So at any given moment I may be in the midst of an assigned free writing session listening to what’s happening in the classroom while also popping into the Facebook chat. And then I might shift to reading my notes and jumping into the class discussion while referring to the readings themselves (texts open on the desk), write some notes in Scrivener, and read something in Facebook that makes me laugh or ponder or some of both. Or I might be focused on the classroom itself as someone else or the instructor offers thoughts. It’s a remarkable multimodal and multimedia experience that requires a handiness with VoIP, social media, word processing, typing, listening, talking in a mic and generally paying attention the whole time.

In short, it’s a lot of fun! It fits the 21st century’s short attention spans while simultaneously enabling deep, focused discussions on very complicated concepts. It keeps me entirely engaged and tires me out, but it also offers something I look forward to each week.

The first issue I think I’ll write on in this class—other than the reading and research notes I’m taking—is the role of technology in the composition classroom. Here, in a survey course intended to cover theoretical approaches to English studies, technology makes it doable. I’ve already discovered that Scrivener keeps me more organized and on-task than Word or Google Docs. And this blog thing, well, it fits the bill, too. But there are considerable obstacles to be overcome that I do not wish to minimize. I am technophile. Technophobes will not likely find these tools as useful or interesting as a technophile. Which suggests that part of the role of technology in the composition classroom has to addressed at an entirely personal level. For me, personally, it’s a delight. Sometimes a little more frenetic than I’m entirely comfortable with, but that’s a stretching and growing experience, not a painful experience to be avoided.

And it’s definitely a more engaging experience for me than the in-person graduates seminars I attended as a master’s-level student. Those seminars could be deadly silent as we each worked to avoid eye contact with each other and the professor, hoping we’d get out of sharing. In this classroom, we’re all engaged. We’re vocal and verbal; we’re even loquacious! But we have interesting insights that we want to hear from each other, and I think that’s the significant different between the experience at the master’s level and the doctoral level. We believe we have something to contribute, so we do so. Yes, the technology we’re engaged with is deliberately interactive and invites participation, but so does a seminar.

I may be so bold as to suggest that the back channel contributes to that level of confidence. In a space where we can’t always see facial cues and other nonverbal communication, we receive affirmation from each other in the back channel. We discover we have something to contribute because we encourage one another with continual comments throughout the evening.

There’s much to be digested and considered—self-reflexivity has a long tradition in English studies, and I intend to join right in.